JOHonduras: U.S. Policy and the Making of a Narco-State

March 20, 2024 Honduras, Narco Trial, US Meddling

“THE PEOPLE’S INDICTMENT OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT IN THE MAKING OF A NARCO-STATE IN POST-2009 COUP HONDURAS”

Critical Perspectives on Democracy + Media Lab, University of California Berkeley

School of the Americas Watch

March 14, 2024

https://thepeople-v-usgov.shorthandstories.com/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=b7f76e7d-e9d3-4bb7-8f8e-03882b5d64ed

Over a period of twelve years (2010-2022), the United States Government collaborated with a politically corrupt drug trafficking regime in Honduras to create an environment conducive to North American business and military interests. This raises critical questions about the delicate balance between economic objectives and democratic principles in U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America.

In the federal court case U.S.A. v. Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH), the U.S. Government exercised its jurisdiction to administer justice against the former President of Honduras and a U.S. ally. On March 8, 2024, JOH was found guilty of international drug trafficking and weapons charges.There is, however, a glaring omission as the U.S. fails to acknowledge its longstanding political, military, and financial support for JOH. A closer examination of U.S. foreign policy and actions reveals a troubling yet historical pattern of U.S. Government influence, involvement, intervention, and impunity in Honduras.

This “People’s Indictment,” exclusively under the jurisdiction of public opinion, charges the U.S. Government with undermining Honduran democracy and aiding JOH’s antidemocratic rule, which transformed Honduras into a narco-state under JOH. By aligning with the JOH administration and providing military support, the U.S. Government strategically positioned itself to benefit from the 2009 military coup in Honduras.

On March 6, 2024, U.S. Prosecutor Jacob Gutwillig stood before the court to deliver his closing arguments in the landmark federal case against JOH. Gutwillig’s words were pointed and damning: “The defendant was the President of Honduras but in the end, he’s just a drug dealer who sent massive amounts of cocaine to this country. Hold him accountable, find him guilty.”This trial marks a significant moment, with the U.S. Government bringing its former ally to justice. However, a critical piece of this complex narrative remains largely unaddressed — the U.S. Government’s own role in JOH’s rise to power, including the provision of funding, weapons, and training to militarized security forces that committed atrocities against Hondurans protesting the erosion of their democracy and civil liberties.

The story extends beyond the sensationalized headlines of narcopolitics, corruption, and the downfall of an ex-head of state to illuminate the U.S. Government’s significant and sustained involvement in the grave injustices committed against the Honduran people and their democracy. By aligning with the post-2009 coup government, the U.S. not only undermined Honduran democracy but also played a part in depriving Hondurans of their rights to democratic processes and sovereignty. This collaboration paved the way for the exploitation of Honduran labor and resources, catering to the long-term economic interests of North American businesses. This chapter in the saga reveals a troubling paradox in U.S. foreign policy — a quest for justice that conveniently overlooks its own complicity in fostering a regime that compromised the very democratic values it purports to uphold.

U.S. Attorney General Merrick B. Garland, Administrator Anne Milgram of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and U.S. Attorney Damian Williams for the Southern District of New York announced the indictment against JOH on April 22, 2022. Source: Department of Justice Press Conference

Anne Milgram, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Administrator: “The DEA’s multi-year investigation revealed that Juan Orlando Hernández, the former President of Honduras, was a central figure in one of the largest and most violent cocaine trafficking conspiracies in the world. Hernández used drug trafficking proceeds to finance his political ascent and, once elected President, leveraged the Government of Honduras’ law enforcement, military, and financial resources to further his drug trafficking scheme.”

United States of America

– v. –

Juan Orlando Hernández

Former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández attends Manhattan federal court to answer U.S. drug and weapons charges in New York, U.S., May 10, 2022 in this courtroom sketch. Credit: Jane Rosenberg for Reuters

On February 15, 2022, Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) was arrested at the request of the U.S. Government and later extradited to the U.S. in April of the same year. Throughout his eight-year presidency, he maintained a close alliance with the U.S., despite increasing allegations of human rights abuses, corruption, and links to drug trafficking. His brother and former Honduran Congressman, Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, is currently serving a life sentence in the U.S. after being found guilty in 2019 of cocaine smuggling as part of the same criminal conspiracy. If convicted, JOH also faces the prospect of life imprisonment for his role in orchestrating a U.S.-bound cocaine trafficking operation through Honduras. This operation exploited Honduras’ law enforcement, military, and financial sectors, transforming Honduras into a narco-state.

Former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, center in chains, is shown to the press at the Police Headquarters in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, Feb. 15, 2022. Source: National Police of Honduras

Originally, the federal criminal case involved JOH and two other co-defendants: his prominent security officials, Former National Police Official Mauricio Hernández Pineda and Former Head of Police Juan Carlos ‘El Tigre’ Bonilla (pictured center to right). Pineda pleaded guilty on February 2, 2024, and Bonilla followed suit on February 6, 2024.

The guilty pleas of Pineda and Bonilla, together with Tony’s life sentence and several other related convictions, including Fuentes-Ramirez’s in 2022, as well as JOH’s trial culminating in his conviction on March 8, 2024, illuminate the complex operations that turned Honduras into a center for international drug trafficking after the 2009 coup in the country.

This publication aims to unravel the intricate web of actions and consequences entangling the governments of Honduras and the United States, critically examining the U.S. Government’s role in fostering a ‘narco-state’ in Honduras—a regime where the state apparatus and illegal drug trade became inextricably linked, a reality that took shape under JOH’s contentious rule with the backing of the U.S. Government. References to the “U.S. Government” herein refer to the amalgamation of official U.S. government departments and agencies that operate cohesively to shape diplomatic relations and formulate U.S. domestic, foreign, trade, and security policies.

Our exploration delves into the evidence and arguments that suggest the United States Government, through its strategic decisions and actions, facilitated the rise of Honduras as a narco-state under JOH. This examination probes into issues of complicity, accountability, and the relentless pursuit of justice. It scrutinizes the actions of a global superpower and the ramifications of its foreign policy choices.

In a 2022 * Tweet/X post ahead of his arrest and extradition to the U.S., JOH proactively attempted to use his alliance and administration’s partnerships with the U.S. Government agencies and departments in his defense.

* ATIC (Technical Agency for Criminal Investigations) and PMOP (Military Police of Public Order) were created during JOH’s tenure and institutionalized military involvement and presence in domestic policing. Other acronyms used: DEA (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration); SOUTHCOM (U.S. Southern Command), “State” in reference to the U.S. Department of State; DOJ (U.S. Department of Justice); FBI (U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigations; CIA (U.S. Central Intelligence Agency); DHS (U.S. Department of Homeland Security).

The People

– v. –

U.S. Government

U.S. Deputy Chief of Mission and Charge d’Affaires of Honduras, Heide B. Fulton with JOH at a 4th of July celebration in 2017. Source: U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa Flickr

This public indictment goes beyond the trial of a single figure, seeking to unravel the deeper dynamics of U.S. Government influence, intervention, and economic ambitions in Honduras.

In this context, “The People” represents a diverse array of perspectives and experiences: those of Hondurans affected by antidemocratic actions, many of whom have endured persecution, violence, insecurity, and forced displacement; students and observers of international relations; everyday taxpayers; and civil society organizations in Honduras and the U.S. and Indigenous groups around the world who have seen their people and lands violated by the crosshairs of narco-state terror and systematic displacement. This collective voice seeks to broaden the narrative beyond the trial of Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH), examining how U.S. government agencies and departments legitimized antidemocratic leadership in post-coup Honduras and delving into the underlying motivations behind these actions by the U.S.

Drawing inspiration from The Permanent People’s Tribunal, this “People’s Indictment” argues that the U.S. Government was complicit in the making of a narco-state, beginning with its support of the 2009 military coup which undermined the Honduran state and democracy, and continuing through its legitimization and support of JOH’s controversial and undemocratic leadership in Honduras.

Central Positions of this People’s Indictment

U.S. Complicity in JOH’s Rise: We assert that the U.S. Government’s backing of JOH was not merely a diplomatic stance but a strategic alignment with broader economic and military objectives in Latin America. This position contends that such support directly undermined Honduran democracy and sovereignty, thereby challenging the integrity and consequences of U.S. foreign policy in the region.

The Hypocrisy of U.S. Democratic Promises: Our position critically examines the glaring discrepancy between the U.S.’ professed commitment to democratic principles and its actual foreign policy conduct, especially following the 2009 coup and continuing into its endorsement of JOH amid allegations of his involvement in narco-trafficking and anti-democratic actions in Honduras. This stance calls for a reevaluation of the U.S. Government’s proclaimed values versus its international actions.

Reinterpreting the Monroe Doctrine for Contemporary Economic Dominance: We argue that the U.S. policy, deeply rooted in the ‘protectionist’ principles propagated in the Monroe Doctrine, continues to exercise hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. The strategy of “nearshoring” manufacturing to Central America, particularly following the coup in Honduras, is viewed as a tactical move to counter Chinese influence and maintain U.S. control over regional resources and labor markets in Latin America. This position highlights a modern adaptation of historic doctrines to serve the contemporary economic and geopolitical interests of the U.S. Government.

Why This Matters

Understanding the nexus between U.S. interests, policy decisions, and the emergence of a narco-state in Honduras following the coup is pivotal for several reasons. First, it illuminates the complexities of international influence and its unforeseen consequences, offering a cautionary tale on the potential fallout of foreign intervention. This understanding is not only crucial for historical accountability but also serves as a safeguard, helping to prevent the replication of similar situations in the future. Moreover, by laying bare this connection, we provide substantive backing to grassroots movements and civic organizations striving for transparency, democracy, and social justice in Honduras. These groups are at the forefront of holding leaders of the Juan Orlando Hernández administration accountable for their actions, while simultaneously endeavoring to ensure that the current administration in Honduras remains committed to its campaign promises of running a progressive government. Recognizing the impact of U.S. policies on Honduras’ political landscape empowers these movements, providing them with the leverage needed to advocate for change and ensure that history does not repeat itself. This contextual backdrop is essential for comprehending the full scope of challenges faced by Honduras today and underscores the importance of international solidarity and informed policy-making in fostering a more equitable and democratic future.

Methods

Our primary data collection involves an examination of publications by U.S. Government departments and agencies, including strategic plans, official statements, press releases, and public memos, particularly those documenting interactions between U.S. government and military leaders and post-2009 coup Honduran officials, with a primary focus on Juan Orlando Hernández.

Additionally, contributors to this publication joined elections observations and human rights accompaniment delegations with the Witness for Peace Solidarity Collective in Honduras. We conducted interviews and heard firsthand insights from Honduran residents and environmental movement leaders. These individuals have experienced the effects of militarization in their communities firsthand, offering invaluable perspectives from their on the ground realities. Our secondary data collection encompasses a wide array of sources, including scholarly literature, reports published by non-governmental organizations, various public media outlets, and case studies that spotlight human rights violations in Honduras. In terms of data and policy analysis, our focus examines U.S. security assistance and foreign policy positions to understand the role of the U.S. Government in the militarization and destabilization of Honduras.

Our analysis employs two theoretical frameworks. The first is Political Economy theory, which we use “to express the interrelationship between the political and economic affairs of the state.” This framework enables us to dissect the complex interplay of political powers and economic interests/structures, shedding light on how they collectively shape state policies and actions. In parallel, our investigation into case studies of communities affected by the surge in militarization after the 2009 military coup is deeply informed by Human Rights theory. This approach is grounded in the concept of “norms that aspire to protect all people everywhere from severe political, legal, and social abuses.” It offers a lens through which to view and evaluate the impacts of these policies on individual rights and freedoms.

Furthermore, our analysis is guided by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This declaration underscores the rights of indigenous peoples “to pursue their own priorities in economic, social and cultural development,”a crucial aspect to consider in understanding the consequences of external political and military actions on indigenous communities. Together, these frameworks form the backbone of our analysis, providing a structured yet flexible approach to exploring the multifaceted issues present in post-coup Honduras.

It is crucial to recognize that the influence of the U.S. Government on Honduras’ socio-political conditions is part of a broader context involving significant roles played by the Canadian government, international financial institutions (such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Interamerican Development Bank), and North American corporations. These entities from the Global North have collaboratively shaped conditions favorable to their interests through military, police, and anti-drug initiatives, notably under Juan Orlando Hernández’s administration and his National Party. While our publication primarily focuses on the U.S. Government’s involvement, the contributions and interests of Canada, IFIs, and North American companies in Honduras also warrant detailed scrutiny. Their complex roles and influences in Honduras, integral to understanding the full scope of external impacts on the country, are subjects for thorough investigation beyond this publication. For more comprehensive insights into the activities of these entities, including additional details on the U.S. Government’s role, we refer readers to the Honduras Solidarity Network’s international public education campaign, “U.S. and Canada On Trial.”

Historical U.S. Involvement In Honduras

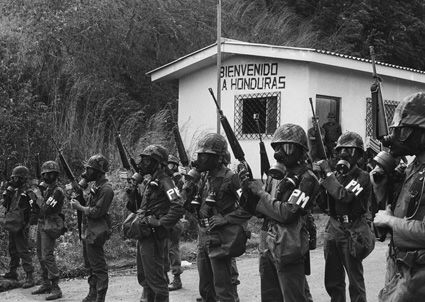

On August 20, 1983, the USS Nassau, a U.S. Navy assault ship, embarked on a mission carrying 180 vehicles and over 1,000 U.S. Army troops to Honduras, supporting Exercise Ahuas Tara. The operation saw the Nassau successfully debark the majority of its soldiers and their equipment at Puerto Cortes and Puerto Castilla, Honduras. This cargo included 24 Black Hawk helicopters, jeeps, trucks, water trucks, and Gamma Goats—a type of off-road vehicle initially developed for U.S. military use in Vietnam. After completing its mission, the USS Nassau returned to Norfolk on September 2. On November 9, the Nassau undertook another voyage to Honduras, this time embarking nearly 1,500 Marines from the 28th Marine Amphibious Unit. Source: 1984 Command History for USS Nassau (1984)

The United States’ historical involvement in Honduras is marked by a complex tapestry of intervention, geopolitical maneuvering, and economic interests. Stretching back to the early 20th century, U.S. troops intervened in Honduras to safeguard U.S. corporate interests in banana plantations, banks, and railroads. Notably, influential figures such as the Dulles siblings wielded their positions as Secretary of State and Director of the CIA to orchestrate counterinsurgency actions from the vantage point of Honduras.

The 1980s witnessed Honduras serving as a strategic base for U.S. operations during the fomentation of right-wing insurgency in Nicaragua following the Sandinista Revolution. Fast forward three decades, and the U.S. found itself backing a coup that ousted the democratically-elected President Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, plunging the nation into widespread political instability and violent state repression. The indomitable thread running through this historical tapestry is the Monroe Doctrine, an embodiment of unbridled U.S. intervention in Latin America and the Caribbean. This policy’s poignant reflection can be traced in the rampant human rights abuses committed in Honduras during and after the 2009 coup, ultimately paving the way for the antidemocratic ascent of Juan Orlando Hernández and the transformation of the nation into a narco-state. This section delves into the intricate details of the U.S. historical context, unraveling the threads that have shaped Honduras’ trajectory.

Monroe Doctrine

As Latin American countries began to gain independence from Spanish colonial rule, the United States, under President James Monroe, introduced the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. This policy aimed to prevent European interference in the Western Hemisphere and establish the U.S. as a regional power. It declared the Western Hemisphere as a “sphere of interest” for the U.S., warning European nations against any intervention in the region, seen as a security threat by the United States.

The Monroe Doctrine marked the beginning of U.S. dominance in Latin America and the Caribbean, laying the foundation for ongoing U.S. involvement in the political, military, and economic affairs of these regions. For over 200 years, it has been a guiding principle in shaping U.S. foreign policy in Latin America.

Station on railway of Standard Fruit & Steamship Co., HondurasW. Rodney Long (born 1898), Transportation Division – Railways of Central America and the West Indies. Washington, Govt. Print. Off., 1925.

In the late 19th century, Honduras, with its abundance of agricultural products, natural resources, and inexpensive labor, drew the attention of both the U.S. Government and corporations. The surging demand for bananas led to the exploitation of Honduras’ agricultural regions. Honduras became known as the “banana republic,” dominated by U.S. corporations, primarily the United Fruit Company and the Standard Fruit Company. By 1929, Honduras was the leading exporter of bananas in the world. These U.S. corporations controlled the country’s agriculture and significantly influenced its domestic politics and governance. Exporters of U.S.-bound bananas, such as the United Fruit Company, financed wars among Honduran elites for concessions to build railroads and develop infrastructure to support their banana exports, while often obtaining tax-free imports. The United Fruit Company epitomized U.S. imperialism in Central America during the first half of the 20th century, stripping Honduras of its natural resources and labor and swaying Honduran politics in their favor.

Agriculture and Trade in Honduras Publication by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Regional Analysis Division tracking U.S. company banana exports from Honduras 1935 -1962.

Dulles Bros

In 1953, a unique historical event unfolded with two siblings assuming leadership roles in both the overt and covert aspects of American foreign policy. President Dwight Eisenhower appointed John Foster Dulles as the Secretary of State and Allen Dulles as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Additionally, the brothers served as legal advisers to the United Fruit Company’s operations in the region. The following year in 1954, the Dulles brothers collaborated to orchestrate a military coup resulting in the overthrow of the democratically-elected socialist president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz.

The U.S. Government used Honduras as a base from which to launch the CIA-organized coup in Guatemala, marking the beginning of decades of state-sponsored genocide against the Guatemalan people. The 1954 CIA-organized coup in Guatemala, along with its utilization of Honduras for counterinsurgency operations, also played a role in suppressing a sixty-nine-day general strike in Honduras. Additionally, it worked to quickly militarize the country and quell uprisings within labor and peasant movements in Honduras.

This clear connection between the U.S. Government departments and agencies, particularly the CIA and the Secretary of State under the Dulles brothers’ leadership, and their ties to U.S. banana companies in the region, played a significant role in shaping their covert and overt operations in Central America. This collaboration exemplifies the convergence of U.S. Government interests aligning with those of U.S. corporations in Central America. The alignment of interests between the government and corporations influenced U.S. policy in the region, prioritizing the protection of American company assets and financial interests. The positions held by the Dulles brothers informed military, policy, and economic decisions in Central America, both overtly and covertly.

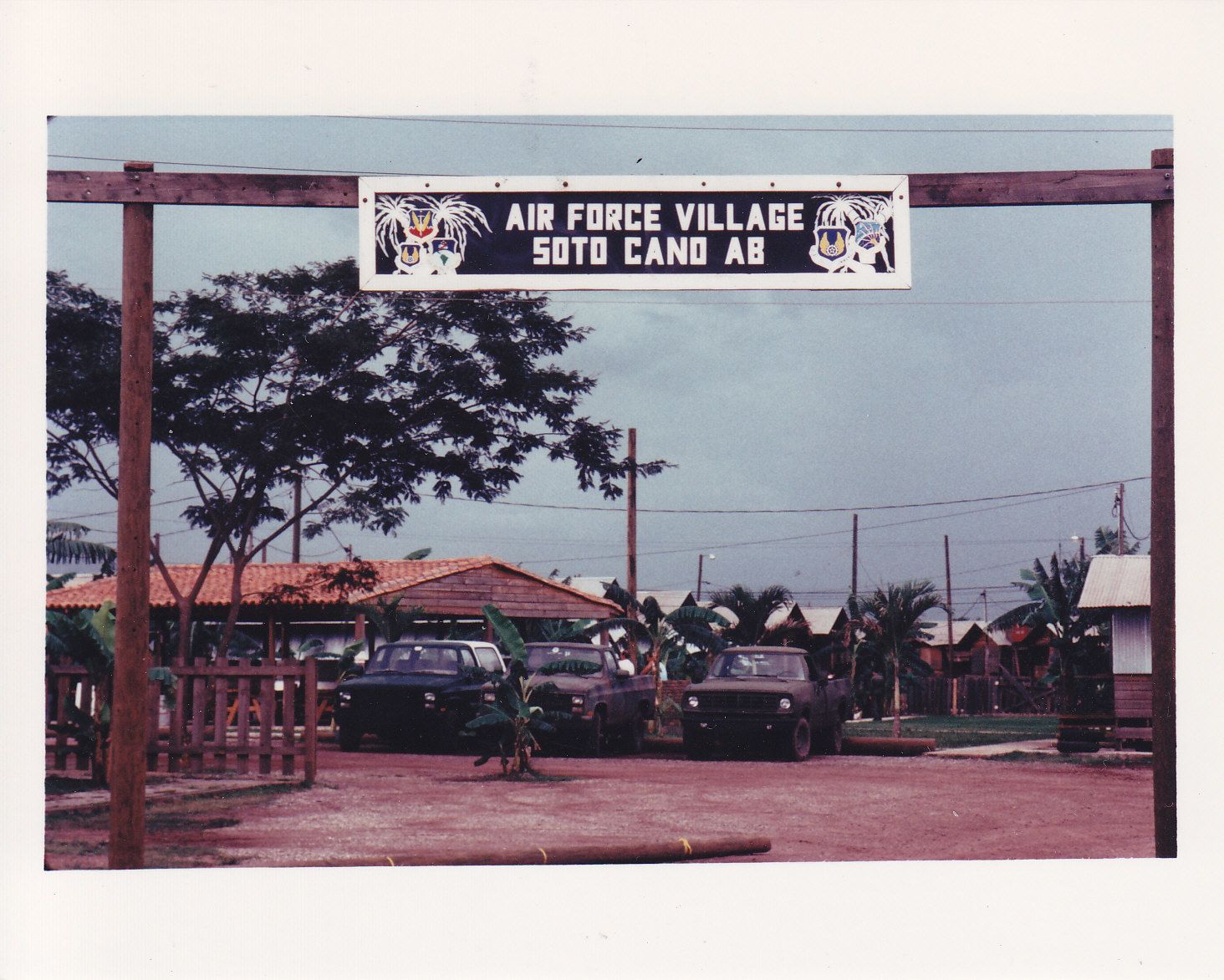

The entrance to the Air Force Village, Soto Cano Air Base, Honduras, September 1989. The Joint Chiefs of Staff created Joint Task Force 11—later renamed Joint Task Force-Bravo—in 1983 to support and control U.S. forces in Central America. Source: U.S. Southern Command, Air Force, NARA

SOUTHCOM

The United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) is one of 11 Combatant Commands under the U.S. Department of Defense. According to SOUTHCOM’s own website, it is “responsible for providing contingency planning, operations, and security cooperation in Central America, South America and the Caribbean (except U.S commonwealths, territories, and possessions). The command is also responsible for the force protection of U.S. military resources at these locations [including] the Panama Canal… It is a joint command comprised of more than 1,200 military and civilian personnel representing the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and several other federal agencies.”

According to a 2020 publication by the U.S. Southern Command titled A History of Joint Task Bravo, the U.S. deepened its military relationship with Honduras, particularly following the Nicaraguan revolution. The U.S. supported Honduran President Roberto Suazo Córdova, capitalizing on pre-existing bilateral relations. Formal U.S. military engagement in Honduras dates back to the 1930s, further solidified by a military assistance agreement signed in 1954, within the context of U.S. military intervention and U.S.-led counterinsurgency operations in neighboring Guatemala.

During the Cold War era, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, Honduras became a staging ground for the U.S.-backed covert military and counterintelligence operations in the region. The U.S government funded proxy wars aimed at preventing the spread of “communism” and Soviet influence in Latin America. Built in 1981, Soto Cano Air Base also known as Palmerola is the chief U.S. military air base in Honduras and the largest U.S. military base in Latin America. The construction of the military base was a key development in the Cold War context that solidified the ongoing U.S. political and military influence of the U.S. Government in Honduras.

Iran-Contra Affair

The Iran-Contra affair, a scandal that unfolded during the Reagan administration in the 1980s, serves as a pivotal illustration of the geopolitical and neo-colonial dynamics involving Honduras. At its core, Iran-Contra involved the secret sale of U.S. arms to Iran, with the proceeds illegally funneled to support the Contras, a U.S.-backed rebel group in Nicaragua fighting the Sandinista government, despite a Congressional ban on such aid. Honduras played a critical role in this scheme as a staging ground for covert operations, underlining its strategic importance to U.S. interests in the region and its susceptibility to becoming entangled in superpower conflicts. This episode highlights the extent to which Honduras has been used as a pawn in broader geopolitical strategies, reinforcing its neo-colonial relationship with the United States.

The outcome of the Iran-Contra affair exposed the complexities of holding powerful figures accountable. While several officials were convicted for their roles in the scandal, many convictions were later vacated or pardoned in the final days of the Reagan presidency and the beginning of George H.W. Bush’s term, raising questions about the accountability of those in the highest echelons of power. The affair left a legacy of controversy over U.S. foreign policy and its interventionist tactics in Latin America, with lasting implications for the region’s perception of American involvement and the sovereignty of captured nations like Honduras.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan appointed John Negroponte to serve as the U.S. Ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985. During Negraponte’s tenure, there was a significant increase in military aid to Honduras, soaring from $3.9 million to $77.4 million. To maintain the flow of aid, the U.S. embassy had the annual task of assuring Congress that the Honduran military was not engaging in severe human rights violations. Negroponte fulfilled this obligation. For instance, in his 1983 report to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he asserted that the “Honduran government neither condones nor knowingly permits killings of a political or nonpolitical nature” and declared that there are “no political prisoners in Honduras.”

According to SOUTHCOM, by 1989 the Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras was “focused on the coordination of more than 15,000 service members from various units in the U.S. who processed through the base for short-term exercises [with] an annual contract budget of more than $20 million. Additionally, the $1.2 million set aside for civic action was the largest in the Department of Defense at the time.”

During the Cold War, Honduras faced various internal and external challenges, including poverty, weak civilian control of government, and the revolutionary wars and political conflict in neighboring El Salvador and Nicaragua. The Honduran government’s economic and geographic position coupled with U.S. funding for proxy wars during the Cold War, made Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras the perfect geopolitical location for U.S. military and economic interests in the region. Honduras is a strategic Latin American outpost for the United States government to keep influence and control of the Western hemisphere, a power dynamic based on the logic of the U.S. Monroe Doctrine.

1989 Newspaper Clipping signaling public and organized resistance to Honduras becoming a permanent military base of the U.S. Government. Source: Ann Arbor District Library

Honduran military officers received training in interrogation and surveillance from the School of the Americas, CIA, and FBI, and these teachings continued in Honduras. In its purported attempt to halt the spread of communism in the western hemisphere, the U.S. Government converted Honduras into its main base for U.S. counterintelligence operations throughout Latin America. One clear example of this is the U.S.-funding of Argentine counterinsurgency experts to train “anti-communist” Central American forces in Honduras in 1981. The influx of hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars, reinforced the power of the Honduran military and the U.S. influence over it.

At the height of the Cold War, Honduras was extensively involved in the U.S.-supported Contra conflict against the Sandinistas. The United States swiftly converted Honduras into a strategic base for launching Contra offensives against Nicaragua. The landscape saw the establishment of numerous airfields, supply depots, and base camps to support Contra forces. The responsibility for this operation involved the rotation of numerous regular U.S. military and National Guard units on duty in Honduras.

Furthermore, U.S. funding not only increased the operational capabilities of Honduran security forces but also trained military units involved in human rights abuses against Honduran civilians. Specifically, weapons and “counterintelligence” combat training provided by the U.S. were used in the violent repression, disappearance, torture, and murder of suspected political dissidents with impunity throughout Honduras. Similar to the death squads of the Cold War era, comparable U.S.-funded and trained militarized units reemerged following the 2009 coup in Honduras, a topic that will be further examined in subsequent sections.

The U.S.-sponsored and trained Battalion 3-16, a Honduran army unit and military death squad, collaborated closely with the CIA during the 1980s. This unit was notorious for its involvement in targeting, politically assassinating, and torturing suspected leftists and government opponents. Sources: The Center for Justice & Accountability ; SOAW Notorious SOA Graduates from Honduras

Military unit Battalion 316 and its leadership became notorious for human rights abuses including torture, abductions, and executions of Honduran civilians. The death squad Battalion 316 was under the command of Honduran military officers and graduates of the U.S. Army School of the Americas, General Alvarez Martinez and Lt. Col. Juan Lopez Grijalba.

The battalion collected intelligence on suspected political opponents of the government and targeted political activists, which included students, teachers, farmers, and unionists. At least 184 individuals were killed or disappeared between the late 1970s and 1988. Anyone suspected of being a political dissident was at risk of being forcibly disappeared.

A wall displaying Honduran victims of forced disappearance in the office of the Committee of Relatives of the Disappeared in Honduras (COFADEH). Source: The Global Learning and Development Centre

In 1995, The Baltimore Sun published a comprehensive four-part series that drew upon interviews conducted with Florencio Caballero, a former member of Battalion 316, and survivors of torture in Honduras. These interviews collectively revealed a portrayal of human rights abuses funded by U.S. taxpayers and exposed the CIA’s role in the operations of Battalion 316: the U.S. Government provided training, equipment, and funding to Battalion 316.

Even though the U.S. Department of State recognized the abuses of Battalion 316 in 1981, the Reagan administration redacted the claims and withheld the full truth from Congress and the American public. As per a report from the CIA inspector general in 1997, officials from the United States stationed in Honduras were cognizant of significant human rights violations committed by the Honduran military but did not accurately report this to Congress. The report, which was extensively redacted, specifically highlights the suppression of sensitive information by the U.S. Embassy during Negroponte’s tenure.

Despite these denials, Battalion 316, purportedly intended to target arms traffickers to Salvadoran guerrillas, evolved into a death squad, supported by extensive cooperation between the Reagan administration and the Honduran military.

“JTF-Bravo’s mission is in transition … due to the end of the Cold War and changes in Central America. You see, democracy has won. Elected leaders have committed themselves and their nations to the democratic process and to economic prosperity.”

-Col. Jack H. Cage JTF-Bravo Commander July 1995

Conclusion

The historical narrative presented in this section unveils a nuanced interplay amongst U.S. intervention, military presence, and geopolitical interests in Honduras. During the Cold War, SOUTHCOM, operating under the U.S. Department of Defense, invested in transforming Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras into a strategic outpost for U.S. military and economic interests.

Originating in 1823 to deter European interference in the Western Hemisphere, the Monroe Doctrine laid the groundwork for over two centuries of U.S. dominance in Latin America. The influence of U.S. corporations, exemplified by the United Fruit Company, significantly shaped Honduras’ politics and governance, showcasing the convergence of government and corporate interests. The collaboration of the Dulles brothers in orchestrating a military coup in Guatemala further highlighted this alignment of interests, leaving a lasting impact on Central America both overtly and covertly.

The establishment and expansion of Soto Cano Air Base during the Cold War solidified U.S. political and military influence in Honduras. Despite being portrayed as a symbol of democracy’s triumph, the base played a pivotal role in U.S.-backed covert military operations. Training programs conducted by the School of the Americas, CIA, and FBI for Honduran military officers in interrogation and surveillance contributed to human rights abuses by Battalion 316. U.S. funding not only amplified the impact of death squads but also fueled internal conflicts, challenging the narrative of democratic progress.

Despite U.S. Colonel Jack H. Cage’s optimistic proclamation in 1995 that democracy had triumphed in Central America, the events leading up to and following the 2009 coup in Honduras challenge this narrative. While SOUTHCOM publicly declared the end of the Cold War in Central America it signaled the evolving mission of the U.S.-led Joint Task Force-Bravo to collaborate with “elected leaders” committed to the “democratic process and economic prosperity.”

SOUTHCOM’s position, as articulated by Colonel Cage, suggests that joint military objectives at Soto Cano Air Base post Cold War aim to promote U.S. Government-endorsed versions of democracy and progress in Honduras. In reality, U.S. military presence and operations in Honduras have wielded U.S. Government influence over the domestic and diplomatic affairs of this sovereign, albeit captive, Central American nation.

The legacy of U.S. involvement in Honduras raises doubts about the claim that democracy unequivocally prevailed with the end of the Cold War. The events surrounding the 2009 military coup, coupled with the subsequent political repression of Hondurans and burgeoning new markets for international business and investment, highlight the complex connections amongst U.S. foreign policy, militarism, and economic interests in Honduras. SOUTHCOM’s narrative of democratic triumph in Central America becomes dubious in light of the complex and enduring impact of U.S. influence in Honduras. This is exemplified in the 2009 military coup and the antidemocratic rise to power of U.S. ally Juan Orlando Hernández.

2009 Military Coup

Honduran soldiers stand guard behind a fence at the presidential palace following a coup d’etat that saw President Manuel Zelaya ousted in Tegucigalpa on June 28, 2009. Photo: Jose Cabezas. Image Source: The Intercept

2009 Military Coup

On June 28, 2009, the democratically elected President of Honduras, Manuel Zelaya, was deposed of his position in a military coup d’état led by U.S.-trained Honduran military generals. Following the military coup, U.S. officials refrained from condemning it as such and provided minimal acknowledgment of the state-led violence against the mass popular social movement that protested the coup on the streets of Honduras in the months that followed. Subsequently, the U.S. State Department actively worked to impede Zelaya’s return to the presidency, disregarding the demands of Hondurans and the international community, who demanded the restoration of democracy and the reinstitution of President Zelaya. Instead, the State Department pushed for new elections and bolstered Juan Orlando Hernández’s post-coup-regime to power.

The 2009 military coup in Honduras not only highlighted the lasting impact of U.S. training and intervention in the region but also set the stage for the turbulent period that followed. The leaders who orchestrated Zelaya’s ousting were U.S.-trained and held authoritative positions in military ground and air operations during the 2009 coup. General Romero Vásquez-Velásquez, a two-time U.S. Army School of the Americas (SOA) graduate (1976, 1984), served as the Chief of the Armed Forces of Honduras. Concurrently, General Luis Javier Prince-Suazo, a member of the SOA class of 1996, held the position of Chief of the Honduran Air Force during the 2009 coup.

On the day of the coup, Zelaya was forced out to Costa Rica via Soto Cano Air Base, which, since 1984, has served as the home base for the U.S.-led Joint Task Force-Bravo. Control over access into and out of the air base during the coup fell directly under the jurisdiction of the Chief of the Honduran Air Force and coup leader, General Prince-Suazo; while tactical and ground operations fell under the leadership of the Chief of the Armed Forces and coup leader, General Vásquez-Velásquez. The Honduran military, on the day of the coup, strategically cut off power across the country, effectively preventing the media from reporting on the unfolding military coup. The affiliation of the coup plotters with the U.S. Army School of the Americas, and their proximity to joint U.S.-Honduras military relations by way of Soto Cano Air Base symbolizes the enduring connection amongst U.S. influence and militarism, forced political transitions (military coups), and state-sanctioned violence against political dissent in Latin America.

U.S. Involvement Amidst Human Rights Abuses

In July of 2009, the Inter-American Human Rights Commission (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS) condemned the serious violations of human rights, including the murder of Honduran protestors and journalists and detention of foreign journalists in Honduras as a result of militarized public repression following the coup. Shocking scenes of military forces clashing with protesters loomed over international news, amplifying global condemnation of the coup and de facto president Micheletti’s government. Non governmental organizations that opposed the coup, including Red Comal, a campesino developmental organization focused on alternatives to dominant agricultural economies, experienced direct attacks from the Honduran military ahead of the post coup elections, showcasing the intensifying crackdown on political dissent. The Honduran military raided the offices of the Red Comal, claiming to have a warrant to search for and confiscate guns or “articles which would threaten people.” The organization’s computers, documents, and cash were seized.

During this period, Honduran civil society faced significant political repression. Post-coup de facto president Roberto Micheletti suspended four articles in the constitution, depriving Hondurans of freedom of transit, public meetings unauthorized by security forces, and prohibiting the media from criticizing the new regime. Up to 4,000 Hondurans were illegally and unjustly detained for protesting the military coup.

In March of 2011, the Inter-American Human Rights Commission held hearings on the post-coup crisis. Various stakeholders, including human rights organizations, activists, and victims, presented evidence of human rights abuses such as beatings, detentions, torture, and executions. The Commission condemned the Honduran government’s actions against various groups, noting the Lobo administration’s difficulty in providing credible responses or justifications. The Commission cited violations including deaths, suppression of demonstrations, arbitrary detentions, and militarization, alongside concerns about increased police and military funding at the cost of health and education. It highlighted judicial corruption following the removal of judges who criticized the 2009 coup and called for profound reforms, urging the Honduran government to cease repression and respect human rights.

The OAS’ Inter-American Commission on Human Rights asserted that serious violations of human rights occurred, including “deaths, an arbitrary declaration of a state of emergency, suppression of public demonstrations through disproportionate use of force, criminalization of public protest, arbitrary detentions of thousands of persons, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and grossly inadequate conditions of detention, militarization of Honduran territory, a surge in incidents of racial discrimination, violations of women’s rights, serious and arbitrary restrictions on the right to freedom of expression, and grave violations of political rights.”

Zelaya remarks on the impact of the United States’ role in the military coup of Honduras: “they’ve created shock forces, psychological war, dirty war.” The people most impacted by the violence of the U.S. Government’s shock forces and dirty war are the people of Honduras who have been fighting, at risk of unjust imprisonment, forced disappearance, and death, protesting the theft of their democratic rights for civic engagement and the destruction of their sovereign republic.

While meetings between U.S. government officials and the post coup Honduran government took place, political repression in Honduras continued unabated. Representatives of the Committee of Relatives of Detained-Disappeared Persons (COFADEH), documented over 120 murders of resistance members, including union leaders. By October 2010, COFADEH documented that a minimum of 157 community leaders associated with the coup resistance movement were forced into exile, a consequence of the ongoing political repression. This escalation in violence, including the targeted murders of journalists, predominantly transpired following the elections, which were mired in controversy yet recognized as valid by the U.S. Government, coinciding with the restoration of diplomatic relations with Honduras. Prominent environmental activists including Miriam Miranda of the National Fraternal Black Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH) was beaten, detained, and charged with sedition during a coup resistance protest.

Despite this turmoil, the U.S. administration lauded President Lobo’s government as a model of democracy and reconciliation, while continuing to fund Honduran security forces. This raised questions about U.S. complicity in the repression and highlighted a discrepancy between its stated commitment to human rights and democracy and its “diplomatic” actions in Honduras.

Presidents Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua, Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, Evo Morales of Bolivia and Manuel Zelaya of Honduras came together in political cooperation and economic integration under the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA). This alliance represented a significant move towards political and economic unity among Latin American and Caribbean nations. Image Source: Peoples Dispatch

Pre-Coup Diplomatic Reforms

Reflecting on his swift forced exile, former Honduran President Mel Zelaya (2006-2009) asserted in a 2019 news interview that U.S. government officials issued an ultimatum in response to his evolving diplomatic alliances with other Latin American countries, alliances that operated beyond the scope of U.S. influence and control. Zelaya revealed this intimidation tactic, stating:

“Well, look,the coup d’état, inexorably, marks a new form of U.S. meddling in our society. Ten years ago [(in 2009)], John Negroponte, [deputy] secretary of state, and President George W. Bush warned me and threatened me, when I was president of Honduras, saying that if I had relations with Hugo Chávez, then I would have problems with the United States. Six months after that warning, I was removed from power and removed from [Honduras]. The problem for the United States is that the friends of those who they consider their adversaries are not their friends. They’ve decided they are enemies of the United States, quite simply, because I was seeking better relations with the south, bringing in oil from Venezuela and getting financing for hydroelectric projects with [Brazil].” – Ousted Honduran President Manuel Zelaya

Zelaya shared a clearer picture of the motivations driving the United States Government to orchestrate a coup d’état in Honduras. In his reflection Zelaya underscores the U.S. Government’s forthcoming action to undermine the sovereignty of Honduras in order to prevent the Central American nation from moving into trade and economic relations with other Latin American nations like Venezuela and Brazil. By 2009, Zelaya integrated Honduras into the Venezuelan-led Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) and Petrocaribe, two regional economic blocs independent of direct U.S. influence and control. Zelaya suggests that the U.S. Government interfered in Honduras’ internal and diplomatic relations to hinder his shift towards economic ties in Latin America. Such ties could have benefited the people of Honduras but would have meant distancing from U.S. influence and control over the nation’s diplomatic and economic affairs.

Zelaya posits that in 2009, the U.S. Government viewed him as an adversary because of his relation with Chavez and Venezuela, against whom the U.S. had targeted sanctions since 2005. The U.S. is keen on projecting its actions onto other countries. While it was clear that Hernández was engaged in the activities for which he has now been convicted, the U.S. concurrently criticized Venezuela. It labeled Maduro a drug trafficker, using this accusation as a pretext for imposing severe sanctions. These measures have led to further destabilization, affecting millions in Venezuela. In 2009, Zelaya’s relationship and political cooperation with Chavez of Venezuela provided sufficient motivation for Negroponte of the U.S. State Department and former U.S. President Bush to issue an ominous warning. This warning foreshadowed Zelaya’s exile through a military coup just a few months later.

Pre-Coup Domestic Reforms

In the lead up to the coup, President Zelaya introduced significant domestic reforms aimed at improving the well-being of Hondurans. These policies included free public education for youth, raising the average minimum wages by 60%, and progressive social welfare measures like cash transfers and free electricity to help reduce absolute poverty. Additionally, as labor and social movement historian Dana Frank analyzes in The Long Honduran Night, Zelaya “opened the door to restoring the land rights of small farmers, and, most importantly, stopped multiple power grabs by the elites, who sought to privatize publicly owned ports, education system, electrical system, and anything else they could get their hands on.”

Zelaya engaged in discussions with left-wing social movements in Honduras that were critical of the U.S. military presence. Many of these groups advocated for a “constituyente,” an elected constituent assembly that if assembled, would have been tasked with crafting a more progressive iteration of the 1982 Honduran constitution; which was formulated and adopted under U.S. guidance at the height of U.S.-funded Cold War operations in Central America.

Zelaya’s choice to hold a non-binding poll, asking Hondurans whether the issue of the constitutional assembly should be included in the upcoming elections, served as the contentious pretext for the 2009 military coup. Despite lacking substantiated evidence, Zelaya’s opponents accused him of trying to amend the constitution to extend his presidency indefinitely. They collaborated with the top two U.S.-trained Honduran military generals, the aforementioned General Vásquez-Velásquez and General Prince-Suazo, to unlawfully remove and exile Zelaya before the constituyente referendum could occur.

To legitimize the military coup and anti democratic takeover, the president of Congress Roberto Micheletti was swiftly inaugurated as de facto and interim president just hours after Zelaya was exiled. Meanwhile, Hondurans took to the streets in protest, resulting in massive demonstrations that paralyzed capital and trade. In retaliation, Micheletti imposed curfews and suspended constitutional rights, moves which would prove indicative of what the next few years in Honduras would look like. Michelitti suspended the freedom of the press and the freedom of transit, and public gatherings not pre authorized by security forces. Michelletti’s post-coup period allowed for arbitrary searches and detentions without warrants. According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, as many as 4,000 individuals were unlawfully detained for participating in or being proximate to post-coup protests and demonstrations.

U.S. Secretary of State shakes hands with Honduran President Mel Zelaya. Image source: Latino USA

U.S. Government Renders Honduran Democracy Moot

The day after the coup, on June 29th, 2009, President Obama initially joined the rest of the world, including the United Nations General Assembly in recognizing Zelaya as the lawful president. However, unlike its counterparts and to the detriment of Honduran democracy, the U.S. Government failed to officially condemn the military coup d’état or call for the reinstatement of President Zelaya.

On July 7, 2009, just ten days after the coup, the U.S. State Department’s approach, particularly that of then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, was calculated. Despite global condemnation and calls for the reinstatement of Zelaya, including a strong stance by the Organization of American States demanding the “immediate and unconditional return of President [Zelaya] to his constitutional duties,” the U.S. Government ignored public outcry. On the contrary, the U.S. Government blocked an Organization of American States (OAS) resolution for immediate reinstatement of Zelaya, pushing instead for mediated negotiations, thus making itself the official arbitrator in the matter.

The United States Government could have made a choice to heed the calls of Hondurans and the international community by using its hegemonic influence to support the return of president Zelaya and the restoration of democracy in Honduras. Instead, Secretary of State Clinton officially announced that “the United States had persuaded both sides to agree to negotiations,” effectively placing the U.S. Government as official arbitrator of said “negotiations.” By shifting the power away from the neutral Organization of American States (OAS) and towards itself, the U.S. Government successfully imposed control over the issue. Unlike the U.S., a majority of the OAS nations called for Zelaya’s presidency to be reinstated. The OAS, in turn, refused to legitimize the post-coup regime.

On November 29, 2009, the U.S. State Department announced its endorsement of elections under the post coup government without the prior reinstatement of Zelaya, thus eliminating any incentive for coup supporters to permit Zelaya to complete his mandate. Declassified documents indicate that Honduran military officers visited Washington to advocate for the coup, and there are indications that they received support and guidance from U.S. military officials.

The official U.S. government position towards post-coup Honduras is further evidenced by Clinton’s biographical recollection in Hard Choices, in which she discussed strategizing a plan to promptly “restore order” in Honduras while confirming the U.S. Government’s preference for new presidential elections. Clinton admitted that she spoke with leaders in the Western Hemisphere about “a plan to restore order in Honduras and ensure that free and fair elections could be held quickly and legitimately, which would render the question of Zelaya moot.” Thus, showcasing that Clinton and the United States Government were less motivated to support Zelaya’s reinstatement instead, opting for a “solution” that would ensure business as usual in Honduras could continue as soon as possible. However, the violent repression present during and leading up to the post coup elections in 2009 indicated otherwise. Upon further inspection, it is now evident that the 2009 coup and elections – and subsequent fraudulent elections of JOH in 2013 and 2017 – undermined the Honduran state and democracy, setting a path that consolidated power with post-coup leadership and culminated in the narco-state.

Looking back at how fiercely the U.S. Government leadership pushed to derail Zelaya’s reinstatement and how quickly they rushed to replace Zelaya’s leadership with new elections in the midst of the suspension of several democratic freedoms, it becomes clear that the 2009 elections were instrumental in consolidating the making of and the legitimization of JOH’s post-coup narco-state. Secretary Clinton and the U.S. Government colluded in rendering the question of democracy and of free and fair elections in Honduras moot.

The 2009 presidential elections, boycotted by Honduran voters in protest, and denounced by the international community , further highlighted the antidemocratic maneuvering towards new elections following the coup. Despite low voter turnout and international questions of legitimacy, the U.S. Government chose to recognize the election results , a decision criticized in Honduras and internationally for undermining the democratic process and the autonomy of Hondurans.

The U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Global Public Affairs ironically celebrated the 2009 elections in a press release stating, “This shows that given the opportunity to express themselves, the Honduran people have viewed the election as an important part of the solution to the political crisis in their country.” Meanwhile, Hondurans were still facing gunfire and illegal imprisonment for exercising their suspended democratic right to freedom of assembly and free speech. It is indispensable to note that the freedom of the press to critique their own government was strategically targeted. Years after the 2009 coup and election, these rights would continue to be repressed by Honduran security forces whom the U.S. Government continued to fund and train.

Simultaneously, as protests and repression of dissidence by security forces continued in Honduras, U.S. officials extended a warm welcome to the new post-coup President of Honduras, Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo. A 2010 press release from the U.S. Embassy quoted U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Craig Kelly congratulating President Lobo on his election and expressing the United States’ willingness to work with his new government. Kelly encouraged Honduran leaders to “support democracy” and normalize Honduras’s international ties.

Porfirio Lobo’s “victory” in these antidemocratic elections – which also made JOH the President of Congress – served to legitimize the new post-coup government and to bolster narco-statesmen to positions of ultimate leadership in Honduras. The quick recognition of the elections by the U.S. Government signaled a prioritization of supporting a president that accommodates U.S. interests over democratic integrity and respect for Honduran sovereignty. In doing so, the U.S.-backed post coup elections ushered in a neoliberal government that would continue to serve ongoing U.S. Government economic interests in Honduras. Having successfully prevented Zelaya’s from returning to the presidency and officially recognizing and legitimizing a new president subservient to U.S. policy interests in Honduras, U.S. Officials under the Obama Administration, declared that “the election [was] a significant step in Honduras’s return to the democratic and constitutional order.”

This period in Honduran history underscores a pattern in U.S. foreign policy where strategic and economic interests often trump stated democratic principles. The United States’ actions, particularly in blocking Zelaya’s reinstatement and endorsing a quick election, suggest an underhanded approach that favors the establishment of a neoliberal government aligned with U.S. economic and military interests. This approach effectively undermines the democratic aspirations of the Honduran people and sets a precedent for future U.S. interventions in the region, paving the way for continued influence and control over Honduras’ political and economic future.

Post-Coup Pivots

According to a July, 2012 report by The Defense Technical Information Center, a repository for research and information of the United States Department of Defense (DOD), stated:

“Upon taking office in January 2010, President Lobo…entered into negotiations with the international financial institutions, and quickly secured an emergency stand-by agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as well as much needed development financing from the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank. Under the agreements, Lobo committed to undertaking structural reforms.”

During Lobo’s contested presidency, he implemented several significant changes that diverged from Honduras’ trajectory under Zelaya’s leadership. Among these divergent actions, Lobo secured loans from the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank, all while pledging to implement severe austerity measures and economic restructuring.

Labor historian Dana Frank reported, “In accordance with U.S. wishes, in February and March [of 2010] the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) reopened the spigot of loans to Honduras for a total of $430 million” and added an “additional $280 million”. However, Latin American governments including Nicaragua, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela refused to recognize Lobo’s government as legitimate which blocked Honduras’ re-admittance into the Organization of American States. In response, during a March 4th 2010 press conference, Secretary of State Clinton said that the U.S. Government shared in the “condemnation of the coup” but urged the global community – and the members of the OAS more specifically, that “…it [was] time to move forward and ensure that such disruptions of democracy do not and cannot happen in the future.” Clinton also stated that she had just notified [U.S.] Congress that [the U.S. Government] would be restoring aid to Honduras.” The $31 million in U.S. funds that had been withheld from Honduras after the coup, and significant additional funds from the U.S.-led international financial institutions would now be made available to the post coup government of Lobo and JOH–who at that time was the president of Congress. Days after Clinton’s announcement, “on March 16, [2010] the Inter-American Development Bank announced it was restoring another $500 million” to Honduras.

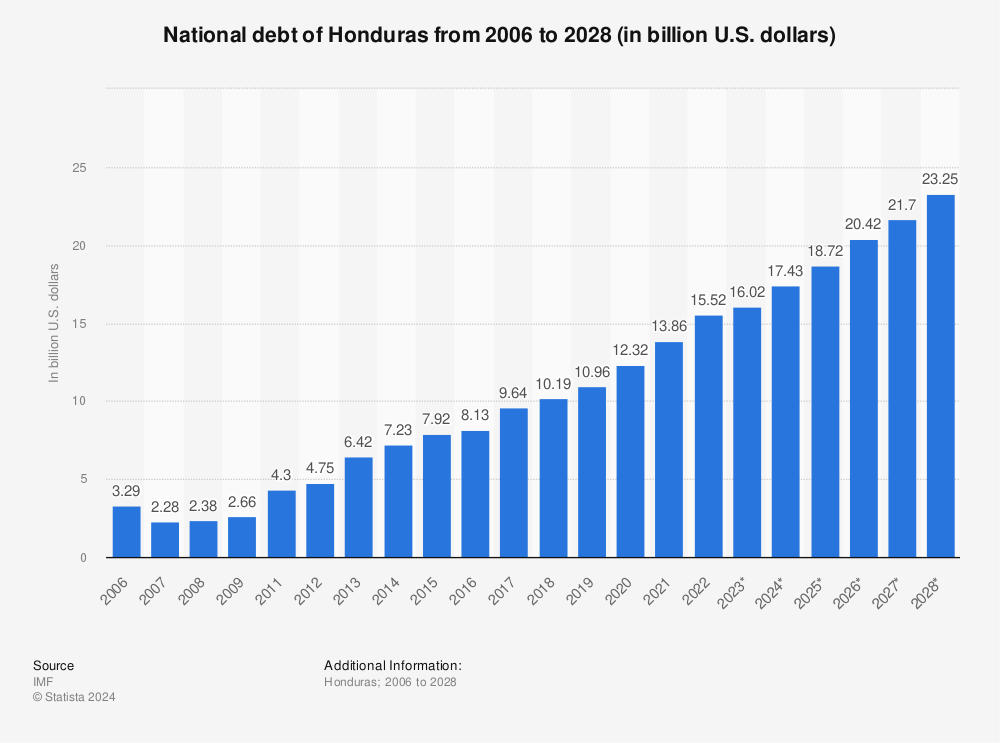

Consequently, this new spigot of loans pushed Hondurans further from the social welfare initiatives and economic sovereignty that Zelaya sought to advance. Rather than maintaining Zelaya’s course, the political shift facilitated by the 2009 coup and subsequent election ensnared Honduras and its people in long-term debt with U.S.-led international financial institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Interamerican Development Bank.

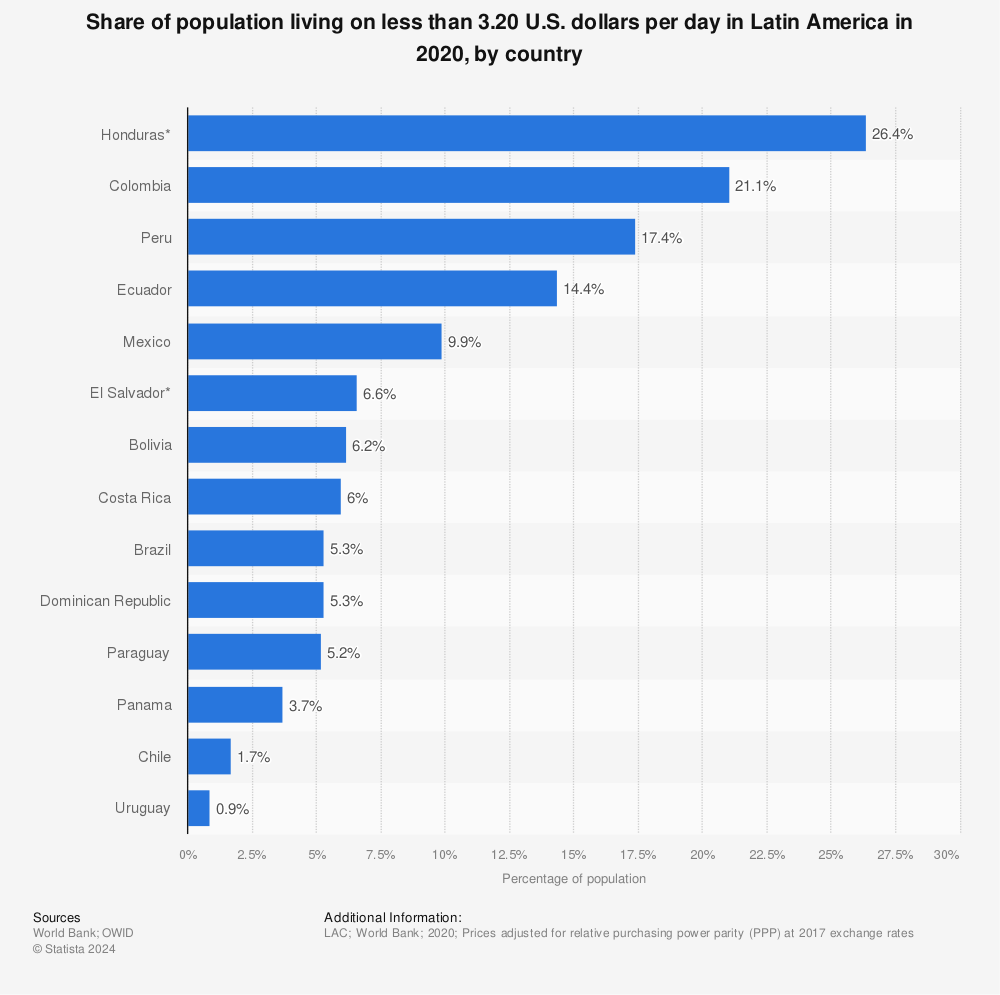

In diametric opposition to Zelaya’s vision of economic prosperity for the peoples of Honduras, Lobo executed harsh structural reforms at the expense of the peoples and natural resources of Honduras, this included a tax reform purportedly designed to increase revenue, an energy reform to more narrowly target subsidies, a reform of public sector pension funds … and a measure de-indexing teachers wages from changes in the minimum wage. This so-called “effort to slow the growth of expenditure on public sector salaries” took a direct cut at the hard-earned incomes and future earnings of Hondurans, who to date continue to be among the most impoverished citizens in the Western Hemisphere.

Table Source: Statista, World Bank Our World in Data

Analyzing Honduras’ national debt data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reveals a significant trend. During Zelaya’s presidency, which began in 2006, there was a notable decline in national debt, reaching a low of 2.2 billion U.S. dollars. However, following the 2009 coup, there was a stark reversal, with debt levels experiencing a dramatic increase. IMF projections indicate that by 2028, the national debt will soar to a staggering 23.25 billion U.S. dollars. This substantial rise can largely be attributed to the economic policies implemented under the tenures of Lobo and Juan Orlando Hernández. The ramifications of this debt are particularly striking when considering that in Latin America, Honduras has the highest proportion of its population living on less than 3.20 U.S. dollars per day. This juxtaposition underscores the immense burden and long-term consequences of the Honduras’ post coup debt crisis.

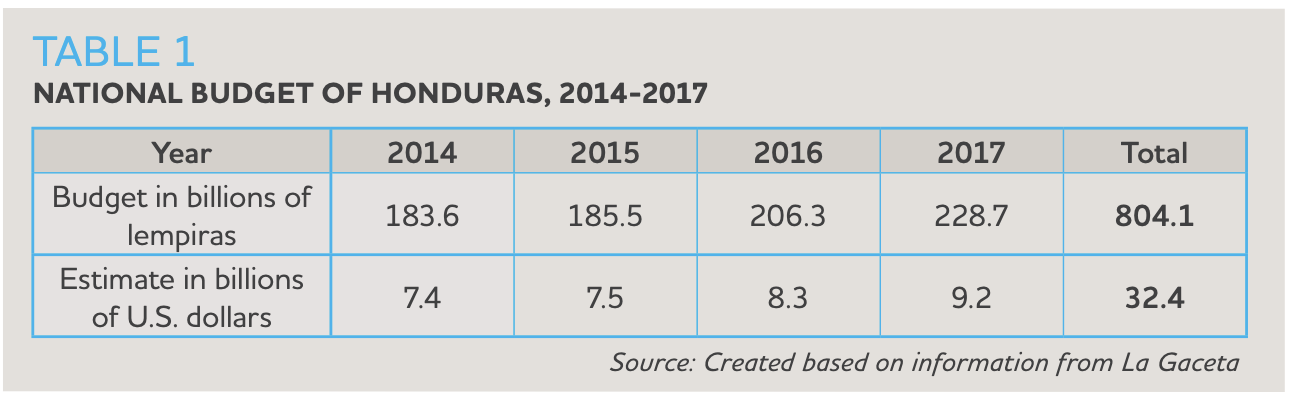

Table Source: Washington Office on Latin America

The allocation of resources in Honduras from 2014 to 2017, under the presidency of Juan Orlando Hernández, sharply tilted towards militarization at the expense of societal stability and the well-being of Hondurans. JOH’s administration earmarked a substantial fraction of the national budget for defense—a total of 23.7 billion lempiras, which amounts to around 947.1 million U.S. dollars. This investment in military might, occurring during a period marked by state repression and widespread impunity, emphasized the JOH government’s prioritization in the country. Evidently, such fiscal choices came at the detriment of critical social services. While the government boasted about declines in murder rates and displayed a fortified military presence in public spaces, essential services like education and healthcare suffered from underfunding. This myopic focus on defense, to the point of treating citizens and organized civil society into potential combatants, not only exacerbated the climate of fear but also left the root causes of instability—such as poverty, inequality, and corruption—largely unaddressed. Far from safeguarding its people, the JOH administration’s spending pattern underscores a disconcerting disregard for the holistic needs of Honduran society, leading to a governance paradigm that prioritized the consolidation of power in the interest of profit over the prosperity of its people.

For unaware taxpayers in the United States, the sobering reality emerges of significant U.S. resources being funneled into “defense” budgets within Honduras. This financial support, as indicated by a rise in Defense Department funding to $4.6 million in FY2014 from $3.5 million for counternarcotics programs in FY2013, underscores a prioritization of militarized security measures over the stability and human rights of the Honduran populace. The implementation of a “Security Tax” in Honduras exacerbates this issue, extracting a portion of incomes to finance the military police, thus drawing criticism for enabling corrupt officials to shield incriminating evidence and avoid prosecution. Moreover, the opacity of the Honduran budget, especially concerning the Security Tax purported to collect between $70 million to $80 million annually, leaves critical questions unanswered about the allocation of these funds and the impact on the Honduran people. The U.S.’s commitment to security assistance, fraught with concerns about human rights abuses and the promotion of damaging economic development, must be scrutinized for its actual contribution to sustainable aid and genuine community support. The true cost of these defense budgets, paid for by U.S. taxpayers and at the expense of impoverished Hondurans, becomes a stark revelation of misplaced priorities in foreign aid and the urgent need for transparent and responsible governance.

Legitimization of Leadership: U.S. Official Meetings with

Juan Orlando Hernández Timeline

Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly meets with Juan Orlando Hernández of Honduras, to discuss bilateral and regional security and economic issues in Washington, D.C., March 22, 2017. “Secretary Kelly highlighted the importance of joint collaboration to combat transnational crime, reduce narcotics trafficking, share information, and promote economic opportunity in the region.” Image Source: Official U.S. DHS Flickr

The timeline below highlights some significant interactions and events between various U.S. Government entities—including the State Department, Embassy, U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Department of Homeland Security, the White House—and the National Party’s leadership in Honduras after the coup, including the now-convicted former president and U.S. ally, Juan Orlando Hernández.

This period is characterized by a convoluted and multifaceted relationship, marked by political upheaval, accusations of narco-state activities, and serious human rights concerns within Honduras which will be explored in-depth in the next section. Central to this account is the ascension and governance of Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) with the support of U.S. legitimization, against a backdrop of political instability and democratic erosion.

The timeline elucidates pivotal moments in U.S.-Honduras interactions, revealing a complex interplay of diplomatic, military, and economic dimensions. It sheds light on the paradoxical nature of U.S. foreign policy in a region of geopolitical significance, where strategic interests often overshadow the stated U.S. government’s commitment to democracy and human rights.

June 2009

The U.S.-backed coup, ousted democratically elected President José Manuel Zelaya. This event set the stage for Hernández’s rise to power and the transformation of Honduras into a narco-state.

2010

January 2010: An official press release from the U.S. Embassy quoted U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Craig Kelly congratulating President Lobo on his election and expressing the United States’ willingness to work with his new government. Kelly encouraged Honduran leaders to support democracy and normalize Honduras’s international ties.

2011

- January 2011: On January 11, 2011, in a meeting with President Lobo and Honduran military leaders, U.S. Army Secretary John McHugh, accompanied by Ambassador Hugo Llorens, reaffirmed the U.S. role in post-coup Honduras. They reiterated commitments to democracy, human rights, rule of law, and civilian control over security forces, emphasizing U.S. cooperation with Honduran armed forces, particularly in combating drug trafficking.

- The Post Coup Honduran government, led by President Pepe Lobo and then-President of the National Congress, Juan Orlando Hernández, launched the Honduras is Open for Business (HOB) initiative. This economic conference, aimed at attracting foreign investment, presented a range of projects alongside new legislation designed to facilitate this investment.

In an official 2011 press release, The U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa highlighted U.S. support for the HOB Initiative, stating that: “U.S. officials welcomed the opportunity to deepen trade relations with Honduras, and to show American companies how investing in Honduras benefits both countries. Approximately 70% of new foreign direct investment in Honduras already comes from the United States. The U.S. is pleased to continue working with President Lobo and his economic team…”

2012

May 2012: During a field operation in Ahuas between U.S. DEA agents and Honduran military personnel, agents killed four unarmed civilians and permanently disabled others. A bipartisan investigation revealed DEA misconduct and cover-up. To date, no one has been prosecuted for these crimes, denying the victims’ families justice.

December 2012: After four Supreme Court judges voted that a police reform law was unconstitutional, Honduran Congress – chaired by JOH – deposed four of the five Supreme Court judges and named new – handpicked – justices the next day. Lobo and JOH-led Congress propose the TIGRES police-military investigative and rapid deployment special forces unit. The TIGRES violently repressed protestors in the following years.

2014

January 2014: Juan Orlando Hernández was inaugurated as President of Honduras. Shortly after, the U.S. DEA learns of his deep involvement with the country’s drug trafficking networks. Despite this, the U.S. continues to support him.

June 2014: U.S. Southern Command’s John Kelly praises Hernández’s anti-narcotics efforts, despite DEA evidence of his drug trafficking activities.

July 2014: President Obama hosted JOH along with the Presidents of El Salvador and Guatemala to address the growing number of unaccompanied minors at the U.S./Mexico border. Source: Obama White House Archives

August 2014: Newly sworn U.S. Ambassador to Honduras, James D. Nealon met with Juan Orlando Hernandez during a ceremony at the presidential palace in Tegucigalpa. Ambassador Nealon was accompanied by Deputy Chief of Mission Julie de Torres, The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mission Director James Watson, and Political Counselor Stewart Tuttle. Addressing the Honduran media, Ambassador Nealon said, “Honduras has no better friend or better partner than the United States and that will not change.”

November 2014: “Ambassador William R. Brownfield, Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, [traveled to Honduras to meet] with President Juan Orlando Hernandez to discuss cooperation on bilateral security and justice issues. Ambassador Brownfield [also visited] U.S. Government-supported vetted units and task forces, where he will participate[d] in an awards ceremony recognizing these units and task forces for their recent successes, including arrests of major drug traffickers.

December 2014: In a 2014 press release, the U.S. DEA published a “Special thanks to the efforts of President of the Honduran Republic Juan Orlando Hernandez Alvarado and other Honduran officials for their cooperation and support during the extradition of the [narco traffickers,] Valle-Valle brothers.”

2015

June 2015: Vice President Biden’s Meeting with Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández at the White House

The White House Office of the President [Barack Obama]: “This afternoon, Vice President Joe Biden hosted Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández at the White House. The Vice President emphasized the Obama Administration’s ongoing support for efforts by Central American governments to address the economic and social factors contributing to increases in illicit migration to the United States. The Vice President and President Hernández reviewed joint efforts to tackle corruption, target transnational criminal networks, and promote economic prosperity and opportunity in Honduras. Specifically on energy, the Vice President emphasized the urgency of continuing implementation on Honduran energy reform and of addressing obstacles to the development of a regional energy market that would provide lower energy prices for the citizens of Central America. The Vice President also discussed the Administration’s $1 billion Fiscal Year 2016 request to Congress for Central America and underscored the importance of working closely with Congress to craft a comprehensive package that addresses the region’s underlying security, developmental, and institutional challenges.”

March 2017

- On Tuesday, March 21, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson Meets with Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández in Washington, D.C.

- Office of the Press Secretary, U.S. Department of Homeland Security: “On Wednesday, March 22, Secretary Kelly met with Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández to discuss bilateral and regional security and economic issues of mutual interest…Secretary Kelly highlighted the importance of joint collaboration to combat transnational crime, reduce narcotics trafficking, share information, and promote economic opportunity in the region.”

On March 22, 2017, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary John F. Kelly and President Juan Orlando Hernández signed an agreement to enhance cooperation involving aviation security between the United States and Honduras.

- On Thursday, March 23, Vice President Pence’s Meeting with President Juan Orlando Hernández at the White House. The Vice President recognized the important progress that Honduras has made over the past two years in fighting violent crime and corruption and strengthening citizen security, including through its police reform efforts.

President Hernández emphasized that Honduras is focused on improving the economy and creating jobs through its Alliance for Prosperity Plan, which will address the root causes that drive illegal immigration.

The Vice President pledged to maintain close relations with Honduras as part of the Administration’s overall engagement with the Northern Triangle of Central America.

November 2017:

- Hernández is reelected as President of Honduras, with significant support from the U.S., despite constitutional limits on reelection and massive popular opposition of electoral fraud.

December 2017:

Speaking on behalf of the U.S. Department of State. Spokesperson Heather Nauert stated “We congratulate President Juan Orlando Hernández on his victory in the November 26 presidential elections…[and] We urge Honduran citizens or political parties challenging the result to use the avenues provided by Honduran law.”

2019

U.S. Southern Command published: “Honduras was the first stop of Faller’s trip. In Honduras Jan. 21 – 22, the admiral met with Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, Minister of Defense Fredy Díaz, and Chief of the Honduran Armed Forces, Maj. Gen. René Orlando Ponce Fonseca to discuss the continuation of both nation’s security partnership. Honduras is a trusted partner in regional efforts to combat illicit traffickers.”

Timeline Conclusion:

The U.S.-Honduras relationship during Juan Orlando Hernández’s (JOH) tenure highlights the impact of political dynamics in both nations. From 2012 to 2016, policies from the Obama administration aligned with significant developments in Honduras, including Hernández’s ascent to the National Congress, and the U.S. approach to Central American migration, characterized by enhanced border security and joint immigration deterrence efforts. The 2014 White House meeting underscored Hernández’s pledge to cooperate on regional challenges, especially in areas of migration and counter-narcotics efforts.

As Obama’s term concluded, U.S. policy and strategic interests in Central America were highlighted by a Guatemala City conference and significant visits by U.S. officials to Honduras. This period also saw controversial developments in Honduran politics, including Hernández’s re-election bid, raising questions about U.S. involvement in legitimizing JOH’s unconstitutional and antidemocratic regime.

The transition to Trump’s administration (2017-2020) intensified U.S.-Honduras relations, evident in more personal engagements and Hernández’s frequent interactions with top U.S. officials. This phase underscored a growing U.S. commitment to Honduras, reflecting the strategic interests of both administrations as exemplified by JOH’s meetings with Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Notable officials from migration-based agencies become more involved with Juan Orlando Hernández. During his tenure, JOH also met with the Director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Homeland Security.

By 2021, the spotlight on Hernández’s alleged drug trafficking links and his brother’s legal issues led to a noticeable decline in high-profile diplomatic meetings, signaling a shift in the public visibility of U.S.-Honduran relations.

U.S. Security Assistance

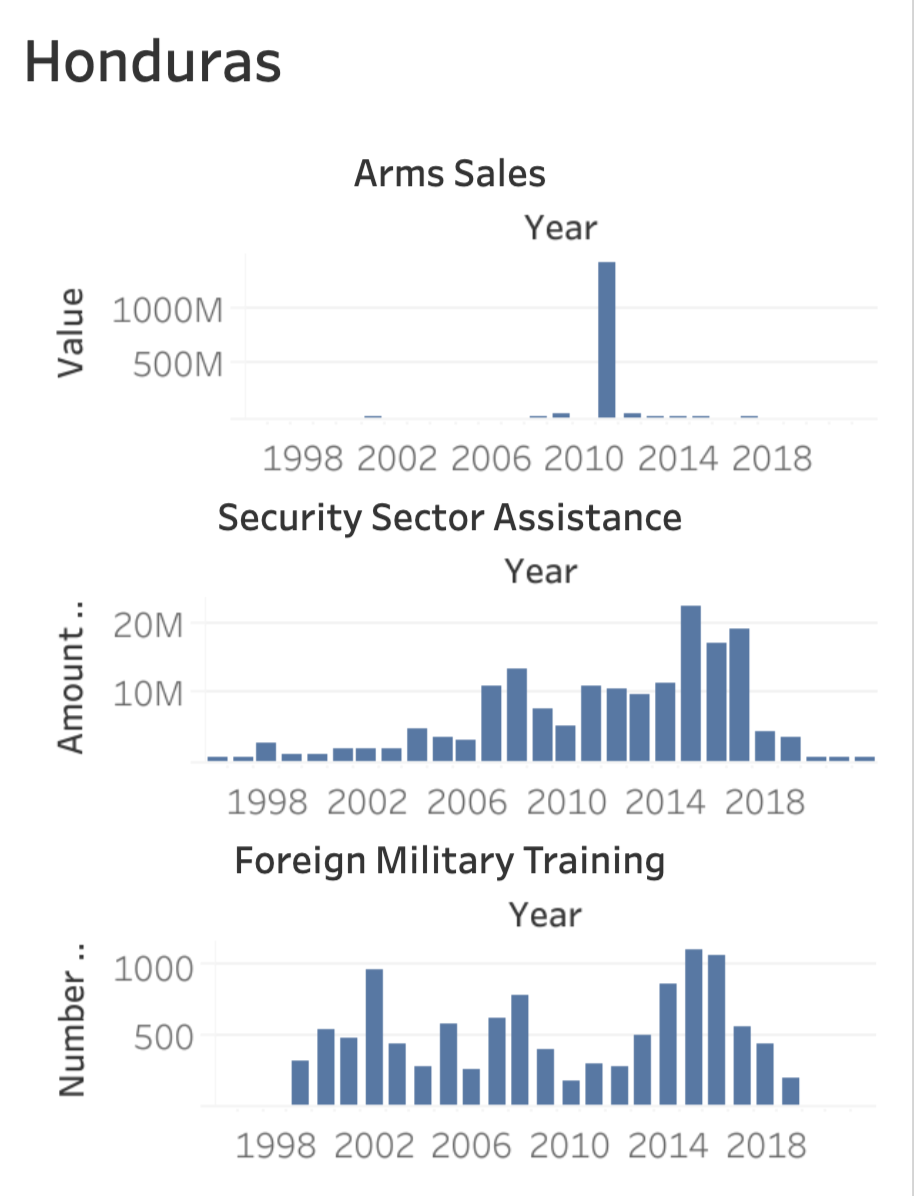

Table Source: U.S. Security Assistance

Human Rights

From 2009 to 2021, under the post-coup leadership of the National Party of Honduras and Juan Orlando Hernández, Hondurans experienced significant violations of their civil and human rights and a significant loss of land and natural resources to private and transnational companies. This period was marked by the rampant privatization and exploitation of land and water, and the erosion of social security, healthcare, education, labor rights, and broad human rights protections. The neoliberal and authoritarian policies enacted by Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) and the National Party facilitated an environment conducive to unlawful constitutional manipulations and an unhealthy reliance on military power. The “Honduras is Open for Business” initiative is a glaring example of such policies, creating pathways for global corporations and the economic elite to usurp control over vital Honduran resources – ranging from rivers to collectively owned lands and even burial sites. The results are described by those directly experiencing the impact such as The Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), as well as NGOs such as EarthRights International, and allies such as the Honduran Solidarity Network.