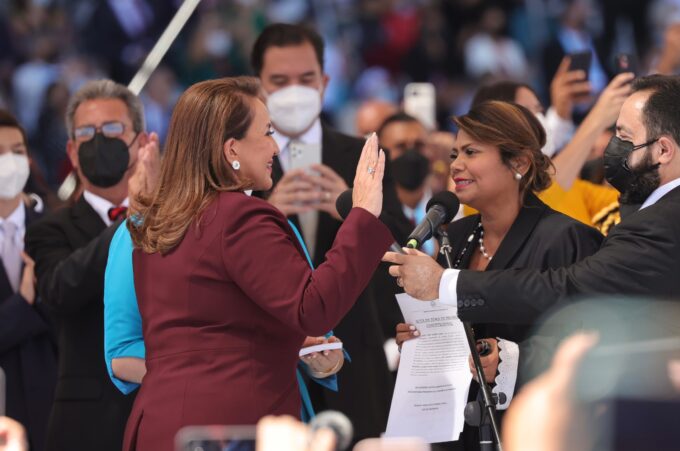

After narrowly losing elections in 2013 and 2017, Xiomara Castro and her social democratic Freedom and Refoundation Party (Libre) won the next set of elections such that, as of January 2022, she was Honduras’s new president. The defeated National Party had presided over worsening corruption, electoral fraud, poverty, and violent repression for 12 years – President Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH), for eight of them.

The U.S. government played a part in the military coup that in June 2009 removed President José Manuel Zelaya. He is President Casto’s husband and longtime “coordinator” of the Libre Party. Now the United States is promoting another coup.

Interviewed by media outlet HCH TV on August 28, U.S Ambassador in Honduras Laura Dogu stated that, “We are very concerned about what has happened in Venezuela. It was quite surprising for me to see the Minister of Defense (José Manuel Zelaya) and the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (General Roosevelt Hernández) sitting next to a drug trafficker in Venezuela.”

The seat-mate was Venezuela’s Minister of Defense Vladimir Padrino López. The occasion was the World Cadet Games of the International Council of Military Sports taking place in Caracas from August 16 on. The U.S. government had charged Padrino López with “conspiring with others to distribute cocaine” and on March 26, 2020 announced bounties for his capture and that of 14 other Venezuelan officials facing drug-related charges.

Responding, Castro immediately declared that “Interference and interventionism by the United States … is intolerable.” Denouncing “U.S. violation of international law,” she canceled Honduras’s 114- year-old extradition treaty with the United States. Honduras has extradited 40 or so individuals to the United States over 10 years for prosecution on drug-related causes. JOH, the best-known of them, was recently sentenced to a 45-year prison term.

Slippery slope

On August 29, President Castro told reporters, “I will not allow extradition be used as an instrument for blackmailing the armed forces … Yesterday they attacked the head of the armed forces and the minister of defense in our country… [such an] attack weakens the Armed Forces as an institution and makes the upcoming process of elections [in 2025] very precarious.”

In a television interview , Foreign Minister Eduardo Enrique Reina indicated Dogu’s comments could set off a “barracks coup” aimed at removing General Roosevelt Hernández. Schisms do exist. A year ago, for example, General Staff head José Jorge Fortín Aguilar’swarned four retired military chiefs to desist from their anti-government activities.

Reina claimed that the extradition treaty, long used as a “political tool to influence the country internal affairs,” could be used “to bring Roosevelt Hernández or Secretary of National Defense José Manuel Zelaya Rosales to trial in the United States, in order to disrupt the Libre Party’s electoral plans.”

Primary elections take place in April 2025 and elections for president and Congress on November 30, 2025. The Libre Party is vulnerable.

The attorney general is investigating secretary of Parliament and Libre Party deputy Carlos Zelaya following his recent acknowledgement that two narco-traffickers in 2013 offered him money for the Libre Party’s election campaign that year.

Implicated in other drug-related crimes, Carlos is the brother of former President José Manuel Zelaya and brother-in-law of President Castro. On August 31, Carlos Zelaya and Defense Minister José Manuel Zelaya each resigned. The latter is Carlos’s son; he and the former president share the same name.

President Castro replaced the resigned defense minister with lawyer Rixi Moncada. She is running for president in the 2025 elections. As such, she would “continue reshaping Honduras’s economic and financial apparatus to fit with the people’s revolution,” according to an admirer.

The situation for Castro and the Libre Party deteriorated even more after September 3 with wide publicity given to a video showing Carlos Zelaya conferring in 2013 with the narco-traffickers. Obtained by InSight Crime and allegedly leaked by the U.S. government, the video is accessible here. It shows the drug-traffickers “offering to give over half a million dollars” to the Libre Party. They mention “previous contributions” to former President José Manuel Zelaya.

On September 6, President Castro condemned Carlos Zelaya’s meeting with narco-traffickers where they “discussed bribes” as a “deplorable error.” That day opposition politicians demanded her resignation. They were leading “more than a thousand Hondurans” in a march through Tegucigalpa.

Fallout and implications

The Libre Party’s loss of political power would jeopardize the already precarious lives of most Hondurans. Government data show a poverty rate of 73.6% in 2021 that fell to 64.1% in 2023. According to UNICEF, “Deprivations are highest in nutrition, followed by deprivations in sanitation, education, water, and overcrowding, respectively.” UNICEF reports that, “The homicide rate was 38.1 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2022, the highest in Central America and the second highest in Latin America.”

Honduran writer, lawyer, political commentator, and Libre Party partisan Milson Salgadooutlines programs introduced by the Xiomara Castro government that promote national development and social rescue.

He cites these: public enterprises recovered from privatization; “high social investment … in the construction of hospitals, repair of educational centers, construction and reconstruction of recreation centers;” extension of the electricity network; and new highways.

The Castro government has funded rural development, provided “educational scholarships at all school levels,” “support[ed] the agricultural sector with loans at the lowest interest rates in history,” provided financial relief for small farmers, “recovered “65,000 hectares of forest,” and provided support for the elderly and disabled.

The U.S. – assisted coup in progress in Honduras is remarkable in two ways. First, it illustrates U.S. reliance on drug war as justifying military and other interventions in targeted Latin American countries. Salgado notes that the United States has “no interest in the fight against narco-trafficking other than to use it selectively as a weapon for blackmailing governments, countries, and people.”

As regards Colombia, the U.S. government invoked the pretext of narco-trafficking as cover for its direct role in combating leftist insurgents. In Peru, a burgeoning drug trade recently prompted the United States to send in troops, most likely out of solicitude for natural resources on tap there. Exaggerated concern about narco-trafficking in Venezuela has rationalized various kinds of U.S. intervention directed at regime change.

Secondly, U.S. strategists altered the device called lawfare that Latin American coup-plotters rely on these days to remove governments not to their liking. That happened in Paraguay,Brazil, Peru, and Ecuador through perverse manipulation of legal norms.

The U.S. gets credit for innovation. Treaties of extradition are legal instruments that, under international law, enable one country to ensure that its criminals staying in another country can be returned for prosecution. It’s a regular legal process that the United States has adapted for Honduras to bring about regime change there.

In any event, government supporters are planning a “big national mobilization” in Tegucigalpa on September 15 “in support of Honduras’s leader, in defense of the homeland’s independence and the building of democratic socialism, and in condemnation of interventionist activities.”